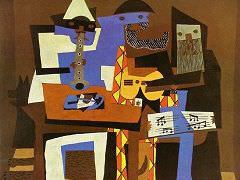

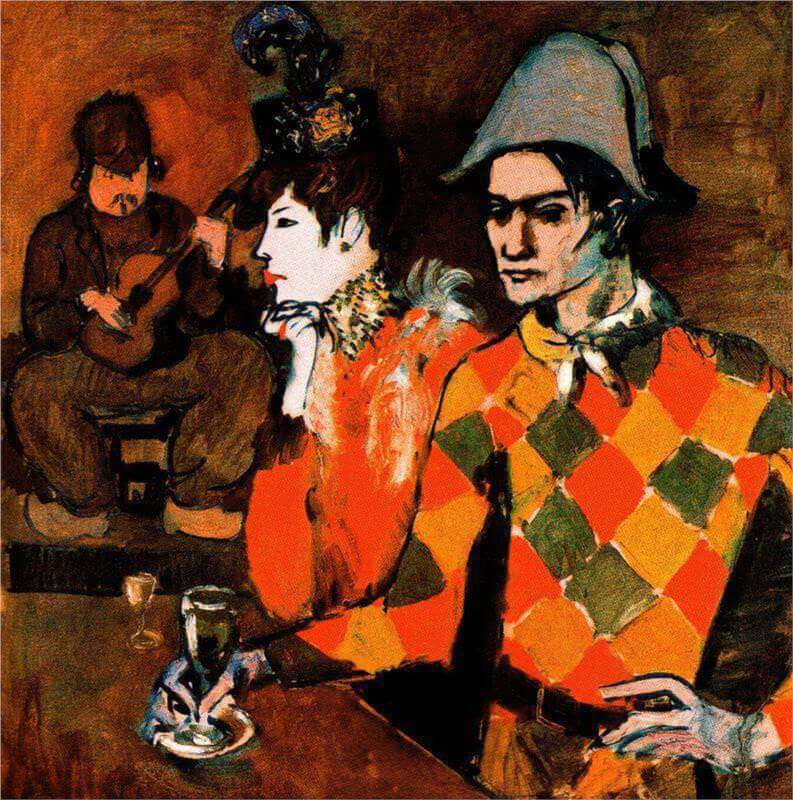

Harlequin with Glass, 1905 by Pablo Picasso

Harlequin with Glass was painted by Picasso in 1905. During this year Picasso's style underwent changes determined in part by personal reasons, yet at the same time reflecting rapid maturation of talent. Leaving behind the joyless world of the Blue Period - Picasso now arrived at the new colors that characterize At the Harlequin with Glass. He is no longer so pessimistic about life; for the first time he begins to celebrate it.

This is one of several paintings in which Picasso documented the life of the performers in circus and carnival which he frequented from time to time while he was living in the so-called Bateau-lavoir in Montmartre. But this painting is more than a discovery of new subject matter. Picasso portrays himself in the figure of Harlequin, identifying himself with his "fellow performers," and with their melancholy, their sense of loneliness. Yet we do not seem quite so hopelessly cut off from the rest of the world here as in the paintings of the Blue Period. There are people clustering around Harlequin, for all that he is on the margin of society, as all artists were in the early part of the century.

We feel that Picasso has come up a bit in the world - living with congenial fellow artists in Montmartre, and having met Fernande Olivier. Besides, the picture shows growing artistic maturity. The shrill colors which characterized Picasso's earliest works in Paris have gone, and with them his indebtedness to such models as Steinlen and Toulouse-Lautrec. The strong reds, yellows, and greens are clearly set off from the warm brownish background; the figures, flat and distinctly articulated, in turn articulate the space. This space is no longer the blank, uninhabitable space of the Blue Period, but a space that is felt - though barely indicated - in which people are yet together, related to each other, if only by listening to the same guitar.

With the first paintings from this new period in Picasso's development, to which this work certainly belongs, Picasso takes mastery of a whole world of his own. No longer obsessed with those purely conceptual figures which abounded in the Blue Period, he now begins to grope timidly for contact with his fellow men. Harlequin's effort to get closer to the world around him, for all his enormous vulnerability, is so sympathetic, so human, that he becomes a compelling symbol. As always in Picasso's art, even in this early work technique and subject are combined in a meaningful whole.