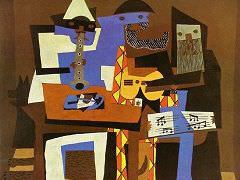

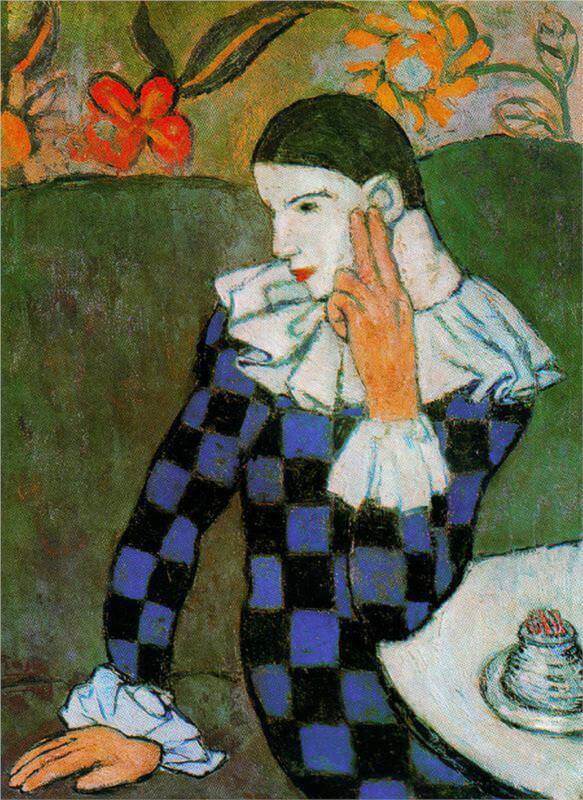

Harlequin, 1901 by Picasso

In 1900, Picasso's pace of style change slowed down noticeably, settled on a limited range of themes and entered into a thoughtful dialogue with two painters he had only just discovered but instantly identified as forces to be reckoned with: Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh.

Picasso had direct access to Gauguin's work through Ambroise Vollard, who had stocked and exhibited Gauguin's paintings and the occasional sculpture since 1893. In Harlequin of summer 1901, the protagonist is treated as a bold chequer-board surface as flat and decorative as the frieze of red and yellow flowers above his head. The contours have been simplified and abstracted but drawn so firmly that the design of the picture locks together like a jigsaw puzzle, and the very heavy, flat application of the paint further emphasizes the unity of the surface. These are the characteristics of the Synthetic style Gauguin developed in Brittany in 1888-89, and passed on to his followers, the Nabis. Indeed, Picasso's painting may owe a lot to Gauguin himself.

Gauguin had the reputation of an heroic outsider so much at odds with bourgeois values that he was impelled to lead the life of a 'savage' in the South Seas - thereby (or so he hoped) escaping 'civilization from which you suffer' and embracing 'barbarism which is for me a rejuvenation'. The fact that every now and then a new shipment of pictures or another letter arrived back in Paris made him an object of unique fascination and romance. Durrio adored him, and Picasso must often have heard colourful stories of his quixotic behavior and his numerous love affairs. The marginalized, hand-to-mouth existence of Harlequin, famed for his amorous intrigues, made him an ideal alter-ego for a wanderer and peintre maudit, but perhaps Picasso also thought of Harlequin as a kind of 'noble savage'. If so, the association of Gauguin's Synthetic style with the image of the sad clown plunged in reflection at a cafe table makes sense, and the painting may be interpreted not just as a homage to Gauguin's radical, decorative style, but strongly suggest that a personal identification underpinned Picasso's admiration.