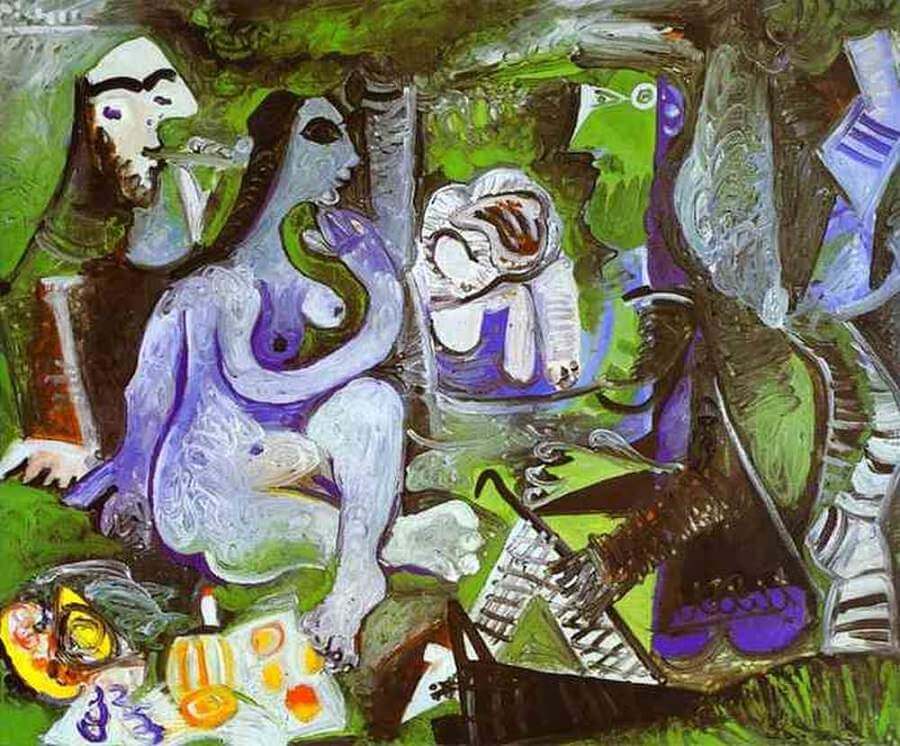

Luncheon on the Grass by Pablo Picasso

For more than two years, from August, 1959, to September, 1961, Picasso worked on this series of paintings, which consists of twenty-seven paintings and many drawings. Once again he found an opportunity to take up a number of his favorite themes.

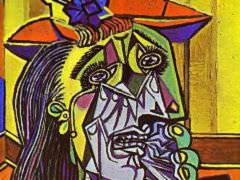

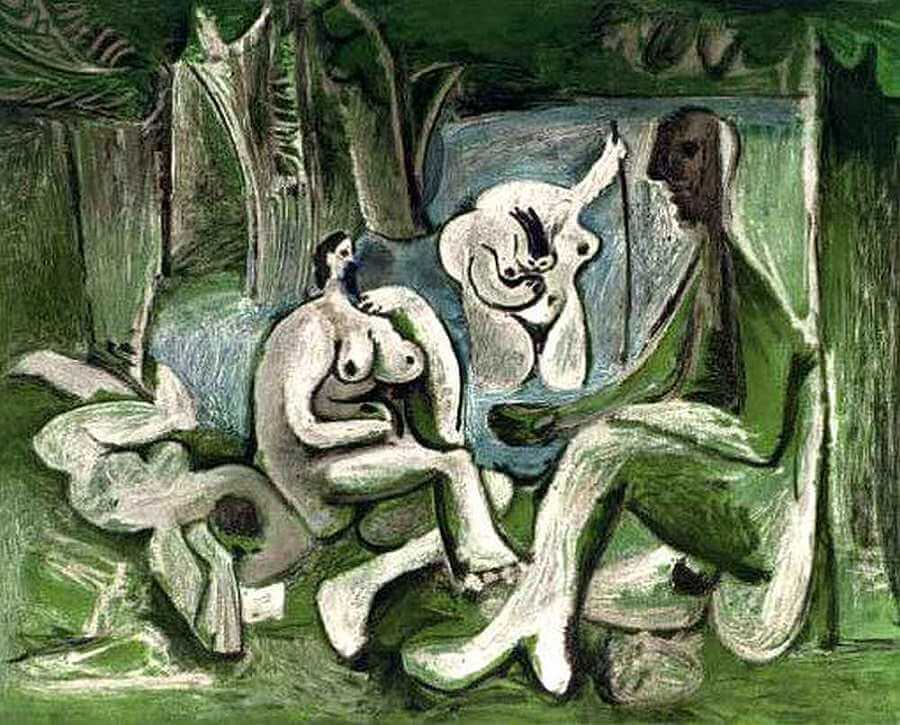

Manet's composition, showing two nudes with two clothed men in a landscape, is itself a kind of variation. Almost exactly 100 years before Picasso treated this theme, Manet, building on a theme taken from an engraving by Marcantonio Raimondi, attempted to translate Giorgione's Concert champetre (in The Louvre) into a contemporary idiom. The Arcadian figures in the work of the great Venetian painter were transformed by Manet into Parisians of his own day, and Arcadia itself took on a new, contemporary form just outside the gates of Paris.

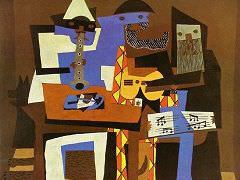

Picasso's variations are of an entirely different kind: he takes Manet's composition as a sort of springboard for his own imagination, which carries him into new, as yet unsuspected directions.

In the course of this work we find Picasso often straying far from his starting point, then coming back to it again, and inventing ever new variations on the theme. To Picasso, Manet's painting - like anything in art or nature - is a theme.

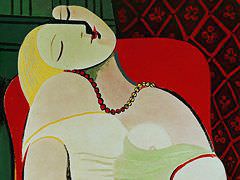

In the painting below (it is the last of one series of variations) Picasso retransforms the model into an Arcadian scene: instead of juxtaposing nude and clothed figures, we have here an idyl with four nude figures, shown near a pond in the subdued green light of the foliage. This brings to mind the themes of the Bather, and Figures on the Beach, which turn up so often in Picasso's works. But, via Manet, a new background has been added to these themes - the dimension of mythology - and the link with nineteenth-century painting has deepened the relationship between the figures, endowing them with greater tension and thus bringing them closer to the spirit of our own days.

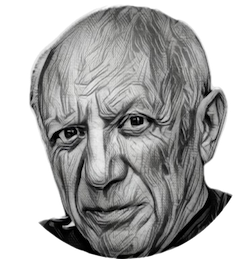

Picasso repeatedly felt tempted to match himself against the old masters. He was conscious of his equality with them, and this feeling gave him the freedom to make whatever use of the old masterpieces he cared to. These paintings show his magnificent ability to transform things and forms alike into new signs, which disclose a new meaning, and in which the image of our time is recorded for posterity.