The Charnel House, 1945 by Pablo Picasso

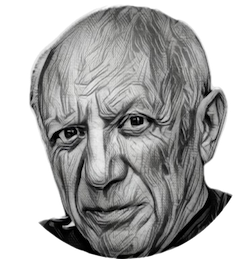

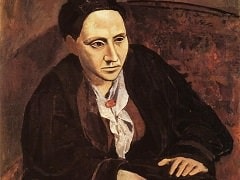

"Art is never chaste," said Pablo Picasso. "Art is dangerous." Picasso was not much of a speech-maker, but he could surely turn a phrase. His characteristic mode of intervention was single-burst point-scoring. He was a riddler. "Braque and James Joyce," he told Gertrude Stein, "are the incomprehensible that anybody can understand." He relished the flip, the quip, the bon mot; he delighted in making mischief. "It's well-hung," he said, of a rival's exhibition. He who invented so much did not invent self-fashioning, but he is the supreme exemplar of artistic self-fashioning in modern times. He was a consummate self-publicist. "You can't be a sorcerer all day long," he remarked knowingly to Andre Malraux. It was but a short step from shaman to showman.

When it came to his art, he was serious as a pope. Towards the end of the second world war, he was goaded by an interviewer on the relationship between art and politics. He interrupted the interview to hurl himself on a piece of paper and scribble a statement, a mini-manifesto, so that he would not be misunderstood. "What do you think an artist is? An imbecile who only has eyes if he's a painter, ears if he's a musician, or a lyre in every chamber of his heart if he's a poet - or even, if he's a boxer, only some muscles? Quite the contrary, he is at the same time a political being constantly alert to the horrifying, passionate or pleasing events in the world, shaping himself completely in their image. How is it possible to be uninterested in other men and by virtue of what cold nonchalance can you detach yourself from the life that they supply so copiously? No, painting is not made to decorate apartments. It's an offensive and defensive weapon against the enemy."

That flash of grandiloquence might be taken as the text for the forthcoming exhibition at Tate Liverpool, Picasso: Peace and Freedom, which sets out to explore the artist as a political being, through the causes he espoused, and above all through his commitment to the French Communist party (PCF), which he joined in 1944, with great fanfare, and never left. Picasso always hoped to go on forever, and he very nearly did. In the course of a long lifetime (1881-1973) he had seen it all, from the Spanish-American war of 1898 to the Cuban missile crisis of 1962. He knew anarchists, bolshevists, socialists, communists, fascists, pacifists, falangists and Stalinists, to say nothing of cubists, futurists, dadaists, surrealists, suprematists, constructivists, destructivists and stridentists. He grew up with monarchism assailed by revolutionary anarchism; he grew old with republicanism served by monopoly capitalism. Ideologically, he had lived.

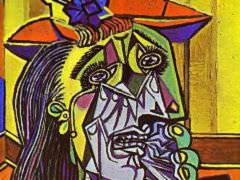

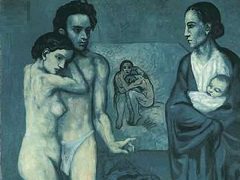

In the matter of the horrifying, he had form. Guernica (1937), then in the United States, was already a cause celebre: "the Last Judgment of our age" or "Bolshevist art controlled by the hand of Moscow", it was gaining in iconic status with each passing decade. At the time of his outburst on the role of the artist, he was working on the most powerful political painting he ever made, The Charnel House (1944-45), the piece de resistance of the Tate exhibition. Picasso himself said that the work was affected by revelations of the real-life charnel houses of the holocaust. In this instance, there is no reason to doubt him.

The pages of his newspaper, the Communist daily L'Humanite, were full of graphic accounts of the camps, complete with illustrations. An article on the crematoria at Natzweiler-Struthof, near Strasbourg, included the macabre detail that the executioners had tied the hands and feet of their victims, like the central motif of the painting, and the heaped corpses in the death zone that constitutes the lower part of the canvas are reminiscent of the first shock photos of the camps - and of Disasters of War (1810-20) by Francisco Goya, images at once unprintable and unforgettable. In the death zone, crucified innocence and clenched-fist defiance grapple with mass killing and dismemberment. The upper zone is less horrific, though no less eerie. Some elements of a contemporaneous still life enter in Pitcher, Candle and Casserole (1945) - the candle, symbol of hope, obliterated. The Charnel House is the offensive and defensive weapon deployed: memento mori, indictment, tribute to sacrifice, howl of despair, and proof positive of lyric poetry after Auschwitz.

The depth of his political engagement remains controversial, however, not least because it is still relatively unexplored. The Tate exhibition, master-minded by Lynda Morris, mounts a spirited defense of the artist as a principled political actor. As its title might suggest, Picasso: Peace and Freedom is almost an apology. Inevitably, it raises more questions than it answers, but the questions themselves are important - what did Picasso stand for? - and in daring to place politics centre-stage (or centre-show) Morris and her collaborators challenge us once again to reappraise this protean and inexhaustible figure.

What are we to make of Picasso politico? He was nothing if not individualistic, but in this respect he exemplifies a general tendency: with few exceptions, the intellectual lives of the artists have not yet been written. Their mistresses command more attention than their mental furniture. This may reflect a certain condescension. Painters in particular are often supposed to be either stupid or vapid, and in any event inarticulate, unable or unwilling to explain themselves; some painters connive at this deception. As the anarchist and abstract expressionist Barnett Newman noted caustically:

The artist is approached not as an original thinker in his own medium but, rather, as an instinctive, intuitive executant, who, largely unaware of what he is doing, breaks through the mystery by the magic of his performance to 'express' truths the professionals think they can read better than he can himself.

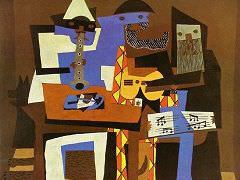

In fact, many painters are lucid expositors and vivid writers, though few are as vivid as Vincent van Gogh. Art and thought (even political thought) are not incompatible after all. But the politics of the palette are seldom as simple as red, white and blue. "It is not necessary to paint a man with a gun," declared Picasso. "An apple can be just as revolutionary."

As always, "Don Misterioso" is a hard case. His convictions are seldom spelled out; his intentions are frequently obscure. With Picasso, it was never one thing or the other. His meaning, like his motivation, was plural, inscrutable, unstable. "A green parrot is also a green salad ... He who makes it only a parrot diminishes its reality. A painter who copies a tree blinds himself to the real tree. I see things otherwise. A palm tree can become a horse. Don Quixote can come into Las Meninas." With such a worldview, mapping belief is a tall order; and interpreting the painting is not likely to yield unambiguous conclusions. On canvas and in conversation, it is unwise to take him too literally. He could never remember whether he had said "I don't look, I find" or "I don't find, I look" - "not that it makes much difference ". Typically, the saying itself was appropriated or adapted from elsewhere - Picassified - in this case from Paul Valery's Monsieur Teste. ("To find is nothing. The trick is to add to what you find.") As his friends and rivals well knew, he was a thievish genius. Pablo Picasso was a great finder. As a painter, he found objects. As a riddler, he found words.

As a sorcerer, he found politics. That is the lingering suspicion - a suspicion that in the end the politics were gesture politics, and not to be taken seriously; that the political beliefs were rather shallow; that communism itself was more or less meaningless to this heedless party member; that the peace-mongering was little more than political posturing; that the trademark dove and all the drawing and lithographing for the cause (well represented in the exhibition) was so much agitprop; that the saluting of Stalin and his henchmen, however idiosyncratic, was at best deluded; that this was at bottom a mercenary affair, whereby the world-renowned painter was exploited by the party for his famous name, his fleet brush, and his financial donations; in short, that Picasso was a useful idiot.

The donations were certainly substantial. It is scarcely an exaggeration to say that Picasso bankrolled the post-war French Communist party, and underwrote various causes associated with it. In 1949, for example, L'Humanite acknowledged his donation of one million francs for striking miners in the Pas de Calais. The party basked in the reflected glory, and pocketed the cash. One of its cells felicitously took his name: Cellule Interentreprise du Parti Communiste Francais Pablo Picasso. His value as figurehead was priceless, as Picasso: Peace and Freedom justly highlights, but it may well be that his greatest contribution was financial. Yet here, too, a note of caution is in order. The donation to the striking miners, touted in the exhibition catalog as an example of Picasso's anarchist principles, was matched by a donation to Fernande Olivier, his former mistress, in return for an undertaking that she would publish no more "Intimate Memories" in his lifetime. Fernande was destitute. She was bought off. Picasso's principles were not much troubled. According to the catalog, "it could be argued that Picasso belonged to the wider 19th-century socialist and anarchist traditions of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Tolstoy, John Ruskin, William Morris and the Independent Labour party of Keir Hardie." That does not seem very plausible. The only thing Picasso had in common with Tolstoy is a work called War and Peace (a tub-thumping mural of 1952, for which he is not remembered). He knew more of hooliganism than anarchism. ("Picasso hooligan" was an epithet bandied around by his friends.) Moreover, one million francs, here or there, was not about to break the bank. Picasso was as rich as Croesus, and the means of production were safe in his hands.

Picasso's "committed" period is said to date from 1944, when he joined the party. His own account is a characteristic piece of self-fashioning. "I came to communism without the slightest hesitation, since ultimately, I had always been with it ... Those years of dreadful oppression [the occupation] showed me that I had to fight not only through my art, but through my own person. I so wanted to return to my native land! I have always been an exile. Now I am one no longer; until Spain can at last welcome me back, the French Communist party opened its arms to me. I have found there all those whom I esteem the most, the greatest scientists, the greatest poets, and all those faces, so beautiful, of Parisians in arms which I saw during those days of August [1944, the liberation]. I am once more among my brothers."

What he found, in this touching fable, was his spiritual home. Yet plighting his troth to the party may have worried him more than he allowed. (The photograph accompanying the announcement is a picture of unease.) Marcelle Braque was convinced that he did not want to take the plunge on his own. Picasso spent a week with the Braques trying to persuade his old comrade from the cubist revolution to come in with him, and make a joint declaration. That would have been still more of a sensation, but Braque remained unmoved, even when appealed to by Simone Signoret. He had as much feeling for the workers of the world as did Picasso. But Braque was not a joiner. Adherence to parties and causes was not for him; only oysters adhere, as he once said. In any case, done like this, it smacked of a publicity stunt. The loathsome occupiers were on the run at last. This was the time for painting, not pantomime. Picasso's announcement was disappointing, possibly, but not unexpected. "It's hardly surprising that he should have joined the Communist party: it gives him a platform." The soap box was as unsuitable as the social whirl. "Picasso used to be a great painter," Braque observed. "Now he is merely a genius."

Picasso adhered, oyster-like, to the end. He attended congresses of Intellectuals for Peace, and even made a speech (against the persecution of his friend the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda), but the conscience-wrenching dramas of the cold war seemed to pass him by. When Soviet tanks crushed the Hungarian uprising in 1956, and the Prague spring in 1968, he had nothing to say. In 1956 Czeslaw Milosz wrote him an open letter. "No one knows what consequences a categorical protest from you might have had ... If your support helped the terror, your indignation would also have mattered." Later in 1968, he drafted and then canceled a statement for an article in Look magazine that tolled the bell on the political being: "I no longer understand the politics of the left and I have no wish to talk about it. I decided long ago that if I wanted to deal with such matters I should have to change profession and go into politics. But of course that is impossible."

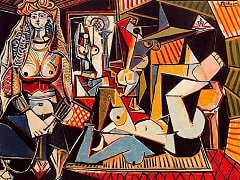

Picasso painted furiously for peace. As art, much of this work was unworthy of him. Picasso: Peace and Freedom propose boldly to circumvent this flaw by co-opting The Women of Algiers (1955), Las Meninas (1957), the variations on Le Dejeuner sur l'herbe (1959-62) and The Rape of the Sabine Women (1962-63), and sundry mothers (for peace) and musketeers (for war), with ingenious suggestions of contemporary political comment. Thus Las Meninas becomes "an indictment of Franco's dictatorship and his royalist aspirations" or "a satirical comment on contemporary Spain, as cruel in its condemnation of the Spanish monarchy as Goya's caricatures". The exhibition is immeasurably enriched, but nagging questions persist.

Picasso is perhaps best seen as a kind of political sleeper. His slavish devotions to the servile French communists notwithstanding, his true commitment was to the Cezanne. "Even a casserole can scream!" he said of The Charnel House. "Everything can scream! A simple bottle! And Cezanne's apples!" In the final analysis, however, he was already spoken for. Pablo Picasso, a painter without peer, lived and died an egotist. A party of one was his ideal station.